Nonimaging optics

Nonimaging optics (also called anidolic optics)[1][2] is the branch of optics concerned with the optimal transfer of light radiation between a source and a target. Unlike traditional imaging optics, the techniques involved do not attempt to form an image of the source; instead an optimized optical system for optical radiative transfer from a source to a target is desired.

Contents |

Applications

The two design problems that nonimaging optics solves better than imaging optics are:[3]

- solar energy concentration: maximizing the amount of energy applied to a receiver, typically a solar cell or a thermal receiver

- illumination: controlling the distribution of light, typically so it is "evenly" spread over some areas and completely blocked from other areas

Typical variables to be optimized at the target include the total radiant flux, the angular distribution of optical radiation, and the spatial distribution of optical radiation. These variables on the target side of the optical system often must be optimized while simultaneously considering the collection efficiency of the optical system at the source.

Solar energy concentration

For a given concentration, nonimaging optics provide the widest possible acceptance angles and, therefore, are the most appropriate for use in solar concentration as, for example, in concentrated photovoltaics. When compared to “traditional” imaging optics (such as parabolic reflectors or fresnel lenses), the main advantages of nonimaging optics for concentrating solar energy are:

- wider acceptance angles resulting in higher tolerances (and therefore higher efficiencies) for:

- less precise tracking

- imperfectly manufactured optics

- imperfectly assembled components

- movements of the system due to wind

- finite stiffness of the supporting structure

- deformation due to aging

- capture of circumsolar radiation

- other imperfections in the system

- higher solar concentrations

- smaller solar cells (in concentrated photovoltaics)

- higher temperatures (in concentrated solar thermal)

- lower thermal losses (in concentrated solar thermal)

- widen the applications of concentrated solar power, for example to solar lasers

- possibility of a uniform illumination of the receiver

- improve reliability and efficiency of the solar cells (in concentrated photovoltaics)

- improve heat transfer (in concentrated solar thermal)

- design flexibility: different kinds of optics with different geometries can be tailored for different applications

Also, for low concentrations, the very wide acceptance angles of nonimaging optics can avoid solar tracking altogether or limit it to a few positions a year.

The main disadvantage of nonimaging optics when compared to parabolic reflectors or fresnel lenses is that, for high concentrations, they typically have one more optical surface, slightly decreasing efficiency. That, however, is only noticeable when the optics are aiming perfectly towards the sun, which is typically not the case because of imperfections in practical systems.

Illumination optics

Examples of nonimaging optical devices include optical light guides, nonimaging reflectors, nonimaging lenses or a combination of these devices. Common applications of nonimaging optics include many areas of illumination engineering (lighting). Examples of modern implementations of nonimaging optical designs include automotive headlamps, LCD backlights, illuminated instrument panel displays, fiber optic illumination devices, LED Lights, projection display systems and luminaires.

When compared to “traditional” design techniques, nonimaging optics has the following advantages for illumination:

- better handling of extended sources

- more compact optics

- color mixing capabilities

- combination of light sources and light distribution to different places

- well suited to be used with increasingly popular LED light sources

- tolerance to variations in the relative position of light source and optic

Examples of nonimaging illumination optics using solar energy are anidolic lighting or solar pipes.

Other applications

Collecting radiation emitted by high-energy particle collisions using the fewest number of photomultiplier tubes.[1]

Some of the design methods for nonimaing optics are also finding application in imaging devices, for example some with ultra-high numerical aperture.[4]

Theory

Early academic research in nonimaging optical mathematics seeking closed form solutions was first published in textbook form in a 1978 groundbreaking book.[5] A modern textbook illustrating the depth and breadth of research and engineering in this area was published in 2004.[1] A thorough introduction to this field was published in 2008.[2]

Special applications of nonimaging optics such as Fresnel lenses for solar concentration[6] or solar concentration in general[7] have also been published, although this last reference by O'Gallagher describes mostly the work developed some decades ago. Other publications include book chapters.[8]

Imaging optics can concentrate sunlight to, at most, the same flux found at the surface of the sun. Nonimaging optics have been demonstrated to concentrate sunlight to 84,000 times the ambient intensity of sunlight, exceeding the flux found at the surface of the sun, and approaching the theoretical (2nd law of thermodynamics) limit of heating objects up to the temperature of the sun's surface.[9]

The simplest way to design nonimaging optics is called "the method of strings",[10] based on the edge ray principle. Other more advanced methods were developed starting in the early 1990s that can better handle extended light sources than the edge-ray method. These were developed primarily to solve the design problems related to solid state automobile headlamps and complex illumination systems. One of these advanced design methods is the Simultaneous Multiple Surface design method (SMS). The 2D SMS design method (U.S. Patent 6,639,733) is described in detail in the aforementioned textbooks. The 3D SMS design method (U.S. Patent 7,460,985), the most advanced design approach to date, was developed in 2003 by a team of optical scientists at Light Prescriptions Innovators.[11]

Edge ray principle

In simple terms, the edge ray principle states that if the light rays coming from the edges of the source are redirected towards the edges of the receiver, this will ensure that all light rays coming from the inner points in the source will end up on the receiver. There is no condition on image formation, the only goal it to transfer the light from the source to the target.

Figure "edge ray principle" on the right illustrates this principle. A lens collects light from a source S1S2 and redirects it towards a receiver R1R2.

The lens has two optical surfaces and, therefore, it is possible to design it (using the SMS design method) so that the light rays coming from the edge S1 of the source are redirected towards edge R1 of the receiver, as indicated by the blue rays. By symmetry, the rays coming from edge S2 of the source are redirected towards edge R2 of the receiver, as indicated by the red rays. The rays coming from an inner point S in the source are redirected towards the target, but they are not concentrated onto a point and, therefore, no image is formed.

Actually, if we consider a point P on the top surface of the lens, a ray coming from S1 through P will be redirected towards R1. Also a ray coming from S2 through P will be redirected towards R2. A ray coming through P from an inner point S in the source will be redirected towards an inner point of the receiver. This lens then guarantees that all light from the source crossing it will be redirected towards the receiver. However, no image of the source is formed on the target. Imposing the condition of image formation on the receiver would imply using more optical surfaces, making the optic more complicated, but would not improve light transfer between source and target (since all light is already transferred). For that reason nonimaging optics are simpler and more efficient than imaging optics in transferring radiation from a source to a target.

Design Methods

Nonimaging optics devices are obtained using different methods. The most important are: the flow-line or Winston-Welford design method, the SMS or Miñano-Benitez design method and the #Miñano design method using Poisson brackets. The first (flow-line) is probably the most used, although the second (SMS) has proven very versatile, resulting in a wide variety of optics. The third has remained in the realm of theoretical optics and has not found real world application to date. Often optimization is also used.

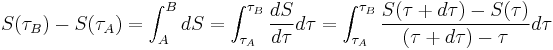

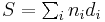

Typically optics have refractive and reflective surfaces and light travels though media of different refractive indices as it crosses the optic. In those cases a quantity called optical path length (OPL) may be defined as  where index i indicates different ray sections between successive deflections (refractions or reflections), ni is the refractive index and di the distance in each section i of the ray path.

where index i indicates different ray sections between successive deflections (refractions or reflections), ni is the refractive index and di the distance in each section i of the ray path.

The optical path length (OPL) is constant between wavefronts.[2] This can be seen for refraction in the figure "constant OPL" to the right. It shows a separation c(τ) between two media of refractive indices n1 and n2, where c(τ) is described by a parametric equation with parameter τ. Also shown are a set of rays perpendicular to wavefront w1 and traveling in the medium of refractive index n1. These rays refract at c(τ) into the medium of refractive index n2 in directions perpendicular to wavefront w2. Ray rA crosses c at point c(τA) and, therefore, ray rA is identified by parameter τA on c. Likewise, ray rB is identified by parameter τB on c. Ray rA has optical path length S(τA) = n1d5 + n2d6. Also, ray rB has optical path length S(τB) =n1d7 + n2d8. The difference in optical path length for rays rA and rB is given by:

In order to calculate the value of this integral, we evaluate S(τ+dτ)-S(τ), again with the help of the same figure. We have S(τ) = n1d1+n2(d3+d4) and S(τ+dτ) = n1(d1+d2)+n2d4. These expressions can be rewritten as S(τ) = n1d1+n2dc sinθ2+n2d4 and S(τ+dτ) = n1d1+n1dc sinθ1+n2d4. From the law of refraction n1sinθ1=n2sinθ2 and therefore S(τ+dτ) = S(τ), leading to S(τA)=S(τB). Since these may be arbitrary rays crossing c, it may be concluded that the optical path length between w1 and w2 is the same for all rays perpendicular to incoming wavefront w1 and outgoing wavefront w2.

Similar conclusions may be drawn for the case of reflection, only in this case n1=n2. This relationship between rays and wavefronts is valid in general.

Flow-line design method

The flow-line (or Winston-Welford) design method typically leads to optics which guide the light confining it between two reflective surfaces. The best know of these devices is the CPC (Compound Parabolic Concentrator).

These types of optics may be obtained, for example, by applying the edge ray of nonimaging optics to the design of mirrored optics, as show in figure "CEC" on the right. It is composed of two elliptical mirrors e1 with foci S1 and R1 and its symmetrical e2 with foci S2 and R2.

Mirror e1 redirects the rays coming from the edge S1 of the source towards the edge R1 of the receiver and, by symmetry, mirror e2 redirects the rays coming from the edge S2 of the source towards the edge R2 of the receiver. This device does not form an image of the source S1S2 on the receiver R1R2 as indicated by the green rays coming from a point S in the source that end up on the receiver but are not focused onto an image point. Mirror e2 starts at the edge R1 of the receiver since leaving a gap between mirror and receiver would allow light to escape between the two. Also, mirror e2 ends at ray r connecting S1 and R2 since cutting it short would prevent it from capturing as much light as possible, but extending it above r would shade light coming from S1 and its neighboring points of the source. The resulting device is called a CEC (Compound Elliptical Concentrator).

A particular case of this design happens when the source S1S2 becomes infinitely large and moves to an infinite distance. Then the rays coming from S1 become parallel rays and the same for those coming from S2 and the elliptical mirrors e1 and e2 converge to parabolic mirrors p1 and p2. The resulting device is called a CPC (Compound Parabolic Concentrator), and shown in the "CPC" figure on the left. CPCs are the most common seen nonimaging optics. They are often used to demonstrate the difference between Imaging optics and nonimaging optics.

When seen from the CPC, the incoming radiation (emitted from the infinite source at an infinite distance) subtends an angle ±θ (total angle 2θ). This is called the acceptance angle of the CPC. The reason for this name can be appreciated in the figure "rays showing the acceptance angle" on the right. An incoming ray r1 at an angle θ to the vertical (coming from the edge of the infinite source) is redirected by the CPC towards the edge R1 of the receiver.

Another ray r2 at an angle α<θ to the vertical (coming from an inner point of the infinite source) is redirected towards an inner point of the receiver. However, a ray r3 at an angle β>θ to the vertical (coming from a point outside the infinite source) bounces around inside the CPC until it is rejected by it. Therefore, only the light inside the acceptance angle ±θ is captured by the optic; light outside it is rejected.

The ellipses of a CEC can be obtained by the (pins and) string method, as shown in the figure "string method" on the left. A string of constant length is attached to edge point S1 of the source and edge point R1 of the receiver.

The string is kept stretched while moving a pencil up and down, drawing the elliptical mirror e1. We can now consider a wavefront w1 as a circle centered at S1. This wavefront is perpendicular to all rays coming out of S1 and the distance from S1 to w1 is constant for all its points. The same is valid for wavefront w2 centered at R1. The distance from w1 to w2 is then constant for all light rays reflected at e1 and these light rays are perpendicular to both, incoming wavefront w1 and outgoing wavefront w2.

Optical path length (OPL) is constant between wavefronts. When applied to nonimaging optics, this result extends the string method to optics with both refractive and reflective surfaces. Figure "DTIRC" (Dielectric Total Internal Reflection Concentrator) on the left shows one such example.

The shape of the top surface s is prescribed, for example, as a circle. Then the lateral wall m1 is calculated by the condition of constant optical path length S=d1+n d2+n d3 where d1 is the distance between incoming wavefront w1 and point P on the top surface s, d2 is the distance between P and Q and d3 the distance between Q and outgoing wavefront w2, which is circular and centered at R1. Lateral wall m2 is symmetrical to m1. The acceptance angle of the device is 2θ.

These optics are called flow-line optics and the reason for that is illustrated in figure "CPC flow-lines" on the right. It shows a CPC with an acceptance angle 2θ, highlighting one of its inner points P.

The light crossing this point is confined to a cone of angular aperture 2α. A line f is also shown whose tangent at point P bisects this cone of light and, therefore, points in the direction of the "light flow" at P. Several other such lines are also shown in the figure. They all bisect the edge rays at each point inside the CPC and, for that reason, their tangent at each point points in the direction of the flow of light. These are called flow-lines and the CPC itself is just a combination of flow line p1 starting at R2 and p2 starting at R1.

Variations to the flow-line design method

There are some variations to the flow-line design method.[2]

A variation are the multichannel or stepped flow-line optics in which light is split into several "channels" and then recombined again into a single output. Aplanatic (a particular case of SMS) versions of these designs have also been developed.[12] The main application of this method is in the design of ultra-compact optics.

Another variation is the confinement of light by caustics. Instead of light being confined by two reflective surfaces, it is confined by a reflective surface and a caustic of the edge rays. This provides the possibility to add lossless non-optical surfaces to the optics.

Simultaneous Multiple Surface (SMS) design method

This section describes

a nonimaging optics design method known in the field as the simultaneous multiple surface (SMS) or the Miñano-Benitez design method. The abbreviation SMS comes from the fact that it enables the simultaneous design of multiple optical surfaces. The original idea came from Miñano. The design method itself was initially developed in 2-D by Miñano and later also by Benítez. The first generalization to 3-D geometry came from Benítez. It was then much further developed by contributions of Miñano and Benítez. Other people have worked initially with Miñano and later with Miñano and Benítez on programming the method.[2]

The design procedure

The SMS (or Miñano-Benitez) design method is very versatile and many different types of optics have been designed using it. The 2D version allows the design of two (although more are also possible) aspheric surfaces simultaneously. The 3D version allows the design of optics with freeform surfaces (also called anamorphic) surfaces which may not have any kind of symmetry.

SMS optics are also calculated by applying a constant optical path length between wavefronts. Figure "SMS chain" on the right illustrates how these optics are calculated. In general, the rays perpendicular to incoming wavefront w1 will be coupled to outgoing wavefront w4 and the rays perpendicular to incoming wavefront w2 will be coupled to outgoing wavefront w3 and these wavefronts may be any shape. However, for the sake of simplicity, this figure shows a particular case or circular wavefronts. This example shows a lens of a given refractive index n designed for a source S1S2 and a receiver R1R2.

The rays emitted from edge S1 of the source are focused onto edge R1 of the receiver and those emitted from edge S2 of the source are focused onto edge R2 of the receiver. We first choose a point T0 and its normal on the top surface of the lens. We can now take a ray r1 coming from S2 and refract it at T0. Choosing now the optical path length S22 between S2 and R2 we have one condition that allows us to calculate point B1 on the bottom surface of the lens. The normal at B1 can also be calculated from the directions of the incoming and outgoing rays at this point and the refractive index of the lens. Now we can repeat the process taking a ray r2 coming from R1 and refracting it at B1. Choosing now the optical path length S11 between R1 and S1 we have one condition that allows us to calculate point T1 on the top surface of the lens. The normal at T1 can also be calculated from the directions of the incoming and outgoing rays at this point and the refractive index of the lens. Now, refracting at T1 a ray r3 coming from S2 we can calculate a new point B3 and corresponding normal on the bottom surface using the same optical path length S22 between S2 and R2. Refracting at B3 a ray r4 coming from R1 we can calculate a new point T3 and corresponding normal on the top surface using the same optical path length S11 between R1 and S1. The process continues by calculating another point B5 on the bottom surface using another edge ray r5, and so on. The sequence of points T0 B1 T1 B3 T3 B5 is called an SMS chain.

Another SMS chain can be constructed towards the right starting at point T0. A ray from S1 refracted at T0 defines a point and normal B2 on the bottom surface, by using constant optical path length S11 between S1 and R1. Now a ray from R2 refracted at B2 defines a new point and normal T2 on the top surface, by using constant optical path length S22 between S2 and R2. The process continues as more points are added to the SMS chain. In this example shown in the figure, the optic has a left-right symmetry and, therefore, points B2 T2 B4 T4 B6 can also be obtained by symmetry about the vertical axis of the lens.

Now we have a sequence of spaced points on the plane. Figure "SMS skinning" on the left illustrates the process used to fill the gaps between points, completely defining both optical surfaces.

We pick two points, say B1 and B2, with their corresponding normals and interpolate a curve c between them. Now we pick a point B12 and its normal on c. A ray r1 coming from R1 and refracted at B12 defines a new point T01 and its normal between T0 and T1 on the top surface, by applying the same constant optical path length S11 between S1 and R1. Now a ray r2 coming from S2 and refracted at T01 defines a new point and normal on the bottom surface, by applying the same constant optical path length S22 between S2 and R2. The process continues with rays r3 and r4 building a new SMS chain filling the gaps between points. Picking other points and corresponding normals on curve c gives us more points in between the other SMS points calculated originally.

In general, the two SMS optical surfaces do not need to be refractive. Refractive surfaces are noted R (from Refraction) while reflective surfaces are noted X (from the Spanish word refleXión). Total Internal Reflection (TIR) is noted I. Therefore, a lens with two refractive surfaces is an RR optic, while another configuration with a reflective and a refractive surface is an XR optic. Configurations with more optical surfaces are also possible and, for example, if light is first refracted (R), then reflected (X) then reflected again by TIR (I), the optic is called an RXI.

The SMS 3D is similar to the SMS 2D, only now all calculations are done in 3D space. Figure "SMS 3D chain" on the right illustrates the algorithm of an SMS 3D calculation.

The first step is to choose the incoming wavefronts w1 and w2 and outgoing wavefronts w3 and w4 and the optical path length S14 between w1 and w4 and the optical path length S23 between w2 and w3. In this example the optic is a lens (an RR optic) with two refractive surfaces, so its refractive index must also be specified. One difference between the SMS 2D and the SMS 3D is on how to choose initial point T0, which is now on a chosen 3D curve a. The normal chosen for point T0 must be perpendicular to curve a. The process now evolves similarly to the SMS 2D. A ray r1 coming from w1 is refracted at T0 and, with the optical path length S14, a new point B2 and its normal is obtained on the bottom surface. Now ray r2 coming from w3 is refracted at B2 and, with the optical path length S 23, a new point T2 and its normal is obtained on the top surface. With ray r3 a new point B2 and its normal are obtained, with ray r4 a new point T4 and its normal are obtained, and so on. This process is performed in 3D space and the result is a 3D SMS chain. As with the SMS 2D, a set of points and normals to the left of T0 can also be obtained using the same method. Now, choosing another point T0 on curve a the process can be repeated and more points obtained on the top and bottom surfaces of the lens.

The power of the SMS method lies in the fact that the incoming and outgoing wavefronts can themselves be free-form, giving the method great flexibility. Also, by designing optics with reflective surfaces or combinations of reflective and refractive surfaces, different configurations are possible.

Miñano design method using Poisson brackets

This design method was developed by Miñano and is based on Hamiltonian optics, the Hamiltonean formulation of geometrical optics[1][2] which shares much of the mathematical formulation with Hamiltonian mechanics. It allows the design of optics with variable refractive index, and therefore solves some nonimaging problems that are not solvable using other methods. However, manufacturing of variable refractive index optics is still not possible and this method, although potentially powerful, did not yet find a practical application.

Conservation of etendue

Conservation of etendue is a central concept in nonimaging optics. In concentration optics, it relates the acceptance angle with the maximum concentration possible. Conservation of etendue may be seen as constant a volume moving in phase space.

Kohler integration

In some applications it is important to achieve a given irradiance (or illuminance) pattern on a target, while allowing for movements or inhomogeneities of the source. Figure "Kohler integrator" on the right illustrates this for the particular case of solar concentration. Here the light source is the sun moving in the sky. On the left this figure shows a lens L1 L2 capturing sunlight incident at an angle α to the optical axis and concentrating it onto a receiver L3 L4. As seen, this light is concentrated onto a hotspot on the receiver. This may be a problem in some applications. One way around this is to add a new lens extending from L3 to L4 that captures the light from L1 L2 and redirects it onto a receiver R1 R2, as shown in the middle of the figure.

The situation in the middle of the figure shows a nonimaging lens L1 L2 is designed in such a way that sunlight (here considered as a set of parallel rays) incident at an angle θ to the optical axis will be concentrated to point L3. On the other hand, nonimaging lens L3 L4 is designed in such a way that light rays coming from L1 are focused on R2 and light rays coming from L2 are focused on R1. Therefore, ray r1 incident on the first lens at an angle θ will be redirected towards L3. When it hits the second lens, it is coming from point L1 and it is redirected by the second lens to R2. On the other hand, ray r2 also incident on the first lens at an angle θ will also be redirected towards L3. However, when it hits the second lens, it is coming from point L2 and it is redirected by the second lens to R1. Intermediate rays incident on the first lens at an angle θ will be redirected to points between R1 and R2, fully illuminating the receiver.

Something similar happens in the situation shown in the same figure, on the right. Ray r3 incident on the first lens at an angle α<θ will be redirected towards a point between L3 and L4. When it hits the second lens, it is coming from point L1 and it is redirected by the second lens to R2. Also, Ray r4 incident on the first lens at an angle α<θ will be redirected towards a point between L3 and L4. When it hits the second lens, it is coming from point L2 and it is redirected by the second lens to R1. Intermediate rays incident on the first lens at an angle α<θ will be redirected to points between R1 and R2, also fully illuminating the receiver.

This combination of optical elements is called Köhler illumination.[15] Although the example given here was for solar energy concentration, the same principles apply for illumination in general. In practice, Köhler optics are typically not designed as a combination of nonimaging optics, but they are simplified versions with a lower number of active optical surfaces. This decreases the effectiveness of the method, but allows for simpler optics. Also, Köhler optics are often divided into several sectors, each one of them channeling light separately and then combining all the light on the target.

An example of one of these optics used for solar concentration is the Fresnel-R Köhler.[16][2]

Compound parabolic concentrator

In the drawing opposite there are two parabolic mirrors CC' (red) and DD' (blue). Both parabolas are cut at B and A respectively. A is the focal point of parabola CC' and B is the focal point of the parabola DD' The area DC is the entrance aperture and the flat absorber is AB. This CPC has an acceptance angle of θ.

The Parabolic Concentrator has an entrance aperture of DC and a focal point F.

The Parabolic concentrator only accepts rays of light that are perpendicular to the entrance aperture DC. The tracking of this type of concentrator must be more exact and requires expensive equipment .

The Compound Parabolic Concentrator accepts a greater amount of light and needs less accurate tracking

For a 3-dimensional "nonimaging compound parabolic concentrator", the maximum concentration possible in air or a vacuum (equal to the ratio of input and output aperture areas), is:

where,  is the half-angle of the acceptance angle (of the larger aperture).[1][17]

is the half-angle of the acceptance angle (of the larger aperture).[1][17]

History

The development started in the mid-1960s at three different locations by V. K. Baranov (USSR) with the study of the focons (focusing cones)[18][19] Martin Ploke (Germany),[20] and Roland Winston (USA),[21] and led to the independent origin of the first nonimaging concentrators, later applied to solar energy concentration.[22] Among these three earliest works, the one most developed was the American one, resulting in what nonimaging optics is today.

There are different commercial companies and universities working on nonimaging optics. Currently the largest research group in this subject is the Advanced Optics group at the CeDInt, part of the Technical University of Madrid (UPM).

See also

- Etendue

- Acceptance angle

- Concentrated photovoltaics

- Concentrated solar power

- Solid-state lighting

- Lighting

- Anidolic lighting

- Hamiltonian optics

References

- ^ a b c d Roland Winston et al.,, Nonimaging Optics, Academic Press, 2004 [ISBN 978-0-12-759751-5]

- ^ a b c d e f g Julio Chaves, Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, CRC Press, 2008 [ISBN 978-1-4200-5429-3]

- ^ William J. Cassarly, Taming light using nonimaging optics, SPIE Proceedings Vol. 5185, Nonimaging Optics: Maximum Efficiency Light Transfer VII, pp.1–5, 2004

- ^ Pablo Benítez and Juan C. Miñano, Ultrahigh-numerical-aperture imaging concentrator, J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, Vol. 14, No. 8, 1997

- ^ W.T. Welford and Roland Winston, The Optics of Nonimaging Concentrators: Light and Solar Energy, Academic Press, 1978 [ISBN 978-0-12-745350-7]

- ^ Ralf Leutz and Akio Suzuki, Nonimaging Fresnel Lenses: Design and Performance of Solar Concentrators, Springer, 2001 [ISBN 978-3-642-07531-5]

- ^ Joseph J. O'Gallagher, Nonimaging Optics in Solar Energy, Morgan and Claypool Publishers, 2008 [ISBN 978-1-59829-330-2]

- ^ William Cassarly, Nonimaging Optics: Concentration and Illumination in Michael Bass, Handbook of optics, Third edition, Vol. II, Chapter 39, McGraw Hill (Sponsored by the Optical Society of America), 2010 [ISBN 978-0-07-149890-6]

- ^ Concentration of sunlight to solar-surface levels using non-imaging optics Nature

- ^ Solid-state lighting requires specialized optical design for optimal performance SPIE

- ^ Pablo Benítez et al., Simultaneous multiple surface optical design method in three dimensions, Optical Engineering, July 2004, Volume 43, Issue 7, pp. 1489–1502

- ^ Juan C. Miñano et. al., Applications of the SMS method to the design of compact optics, Proceedings of the SPIE, Volume 7717, 2010

- ^ Schulz, G., Aspheric surfaces, In Progress in Optics (Wolf, E., ed.), Vol. XXV, North Holland, Amsterdam, p. 351, 1988

- ^ Schulz, G., Achromatic and sharp real imaging of a point by a single aspheric lens, Appl. Opt., 22, 3242, 1983

- ^ Juan C. Miñano et. al, Free-form integrator array optics, in Nonimaging Optics and Efficient Illumination Systems II, Proc. SPIE 5942, 2005

- ^ Pablo Benítez et. al., High performance Fresnel-based photovoltaic concentrator, Optics Express, Vol. 18, Issue S1, pp. A25-A40, 2010

- ^ Martin Green, Solar Cells: Operating Principles, Technology, and System Applications, Prentice Hall, 1981 p.205–206 [ISBN 978-0-13-822270-3]

- ^ V. K. Baranov, Properties of the Parabolico-thoric focons, Opt.-Mekh. Prom., 6, 1, 1965 (in Russian)

- ^ V. K. Baranov, Geliotekhnika, 2, 11, 1966 (English translation: V. K. Baranov, Parabolotoroidal mirrors as elements of solar energy concentrators, Appl. Sol. Energy, 2, 9, 1966)

- ^ M. Ploke, Lichtführungseinrichtungen mit starker Konzentrationswirkung, Optik, 25, 31, 1967 (English translation of title: A light guiding device with strong concentration action)

- ^ H. Hinterberger and R. Winston, Efficient light coupler for threshold Čerenkov counters, Review of Scientific Instruments, Vol. 37, p.1094–1095, 1966

- ^ R. Winston, Principles of solar concentrators of a novel design, Solar Energy, Volume 16, Issue 2, p. 89–95,1974

External links

- Oliver Dross et al., Review of SMS design methods and real-world applications, SPIE Proceedings Vol. 5529, pp. 35–47, 2004

- Compound Parabolic Concentrator for Passive Radiative Cooling